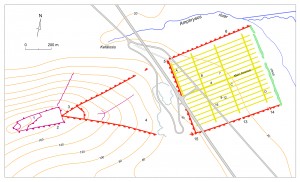

Enclosing an area of 50 hectares, the circuit wall of the lower town was almost 3 kilometres long, fortified with c. 70 towers. The upper town including an akropolis or keep was enclosed by a circuit wall that was also 3 kilometres long, fortified with c. 50 towers. The circuit wall of the lower town lies entirely in the plain, on pleistocene soil. The highest point lies in the southwest, from where the ground slopes downward to the north and the east. The trace of the enceinte can easily be followed on all sides.

Nowadays the South wall manifests itself as a low wall. A layer of rubble and earth, its total width varying from 5 to 14 m, lies on, behind and in front of a large part of the facing blocks. Here and there the facing blocks protrude from the rubble. An area with conglomerate rock to the south of the city wall lies close to the surface an advantageous situation to prevent digging trenches to undermine the city wall.

The West wall has been preserved to a considerably higher level. The West wall may be seen as an extra line of defense between the upper and lower part of the town, in case a potential enemy sees chance to take the upper town. Due to the widening of the National Road in the late 1990’s the entire stretch of the city’s West wall was excavated.

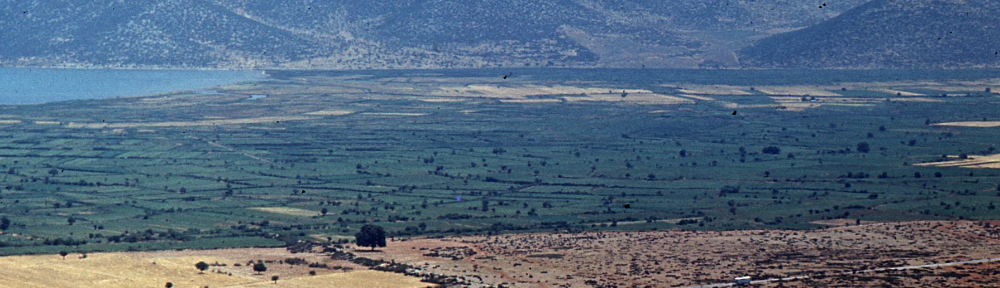

A dirt track indicates the trace of the North wall, stones of which can be seen imbedded in the track here and there. River Amphrysos, fed by the powerful Kefálosis spring and a series of springs near a church dedicated to Áyios Márkos, runs along the north side of this part of the city wall. The low-lying valley and river between the city wall and the Voulokalíva area is a strong natural line of defence.

Of the East wall nothing remains, except for two short stretches. A strip of underbrush marking a difference in height in the terrain and approximately following the outline of the old enceinte was taken to indicate the course of the eastern wall. On the whole, the terrain along the northern and eastern walls is higher on the inside of the wall than on the outside. Along the eastern wall the difference in height is remarkable, being 1 to 2 m. Moreover, the coastal marsh between the East wall and Soúrpi bay is a formidable natural line of defense.

Air photos had already revealed that the two walls of the upper town can be followed from the apex down to about 300 m and 150 m from the south- and northwest corners of the lower town. Although large parts of the two walls are missing, with some effort, the course can be followed in the field as well. Both walls of the upper town present a straight trace with a few slight deviations; well preserved on top of the hill and a course of rubble with the remains of the towers as recognizable ponts further down. There where the walls have disappeared, the terrain has been changed drastically by modern quarries and road construction.

On the slope at a height of 165 m above sea level a cross-wall was built, creating a triangular acropolis, or rather a ‘military keep’ (Winter 1971, 59). This wall is clearly thicker than the other walls. It is rather difficult to study it in detail because part of the wall is now covered by a rubble wall of more recent date, with the exception of the northern part. It should be noted that the cross-wall of the acropolis is the only wall that follows the contour of the terrain.

We assume that there was a large tower or battery where the walls of the upper town converge, and that it was later used as the foundation for the largest tower of the Byzantine fort. From this dominating tower the lower lying terrain at the transition to the spurs of Mount Óthris could be commanded.